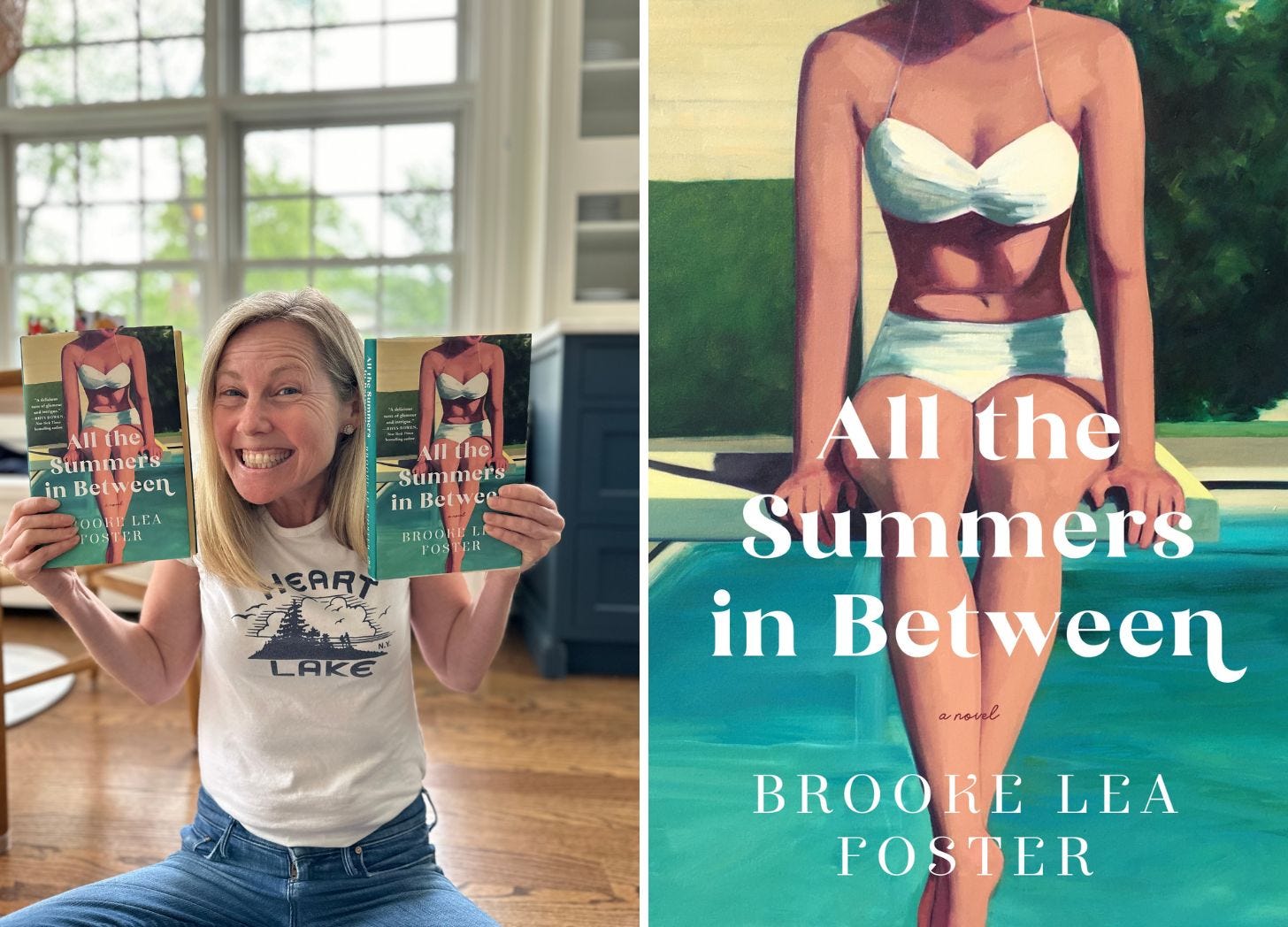

Author Confessions: Brooke Lea Foster

My book is out and the amazing writer Amy Odell of Back Row interviews ME!

We all have that one friend who got away. Maybe the friendship was too good to last. Maybe it just belonged in a certain period of time, a fleeting context of our lives, like college. But what if that friend re-entered your world? This is the question that your regular newsletter host Brooke Lea Foster explores so deliciously in her latest novel, All the Summers In Between. Set in East Hampton, it’s the story of local, working-class girl Thea, who befriends wealthy summer residet Margot. Unfolding over two timelines in 1967 and 1977, we learn the story of their first summer as friends, and why Margot has suddenly reappeared in Thea’s life, in apparently dire need of help. Brooke asked me to interview her in honor of her publication day, and I was thrilled to take her up on it.

As a journalist and author myself at Back Row, I have enjoyed getting to know Brooke over long walks and coffee dates where we trade opinions on books we’ve read and tips for muscling through the often painful, occasionally glorious, inevitably isolating writing process. Though I have been writing narrative nonfiction (I published a biography of Anna Wintour in 2022) and Brooke has been writing novels, I have gained so much wisdom from Brooke in the few years I’ve known her about the book publishing industry, what makes stories addictive, and how to muscle through feeling like I suck at this, among many other things. The principles for good storytelling are the same for both novelists and nonfiction writers alike, and Brooke offers even more great advice in today’s interview. All the Summers In Between is compulsively readable, the kind of book I couldn’t wait to put my kids to bed to get back to each night, and I hope you buy a copy (at your local indie bookstore, if you can).

Ahead, Brooke discusses why she told this story, why she doesn’t outline, and more.

You started your career in media. How did that set you up for fiction writing? Did you feel freed to not have to worry about telling a story through a set of facts?

I spent so many years writing in the voice of magazines and newspapers, and with journalism, writing an article had come to feel like a bit of a formula. Get the opening anecdote, add in a powerful quote, write a “nut” graph and then the body of the piece. I was accustomed to parachuting into different worlds and talking with all different kinds of people, but all my stories were shaped by facts and quotes. I couldn’t just invent a better story to make it more interesting.

But after two decades, I really wanted to flex a different muscle as a writer. I found fiction writing really intimidating, even if I had always dreamed of doing it. Still, I had a novel idea in 2016 that sunk its teeth into me while on vacation with my family in Martha’s Vineyard, and when I sat down to write the opening chapters of what came to be my first book, I’d never felt so free. I started to hear my own voice, rather than the voices of the publications I’d been writing for, and I was astounded that I could take a story in any direction that I wanted!! I could make up facts. I could invent things about people, their quirks, their personality traits, their limitations and their desires. It was insanely fun.

I remember calling a journalist friend at the time and sounding all giddy, saying something like: “You don’t have to wait for a great quote! You just get to make one up.”

This book centers around a friendship (frenemy-ship?) between two women. What made you want to make that a focus of this book?

I’ve always been interested in female friendships, in part, because they can be so hard to maintain. It’s one of the only relationships in our lives where the expectations and rules aren’t clear cut. We know how we’re supposed to act as a wife and a mom, but with our friends, it can be confusing. When are we leaning too much on a friend? How much time is required to keep up a friendship? Should we dig into an existing friend or find a new one?

I made so many of my closest friends when my son was young, and I first moved to the suburbs. In the beginning, I thought of those other young women as “mom friends,” almost like those relationships weren’t as meaningful as the ones I’d made in high school and college. We talked only of our kids and sleep schedules and the tantrum that our toddler had in the candy aisle the day before. But as months slid into years, those friendships evolved, and now that my son is going into high school, I’ve realized that those “mom friends” are my closest friends. We managed to parlay those playground conversations into deep and meaningful ones held over book club discussions or dinners to celebrate one another’s birthdays.

Still, the way that I need those friends is so different than how I needed my friends in my teens and twenties. In those formative years, I looked to my friends the way many of us do: to build us up, help us define our identities, and make us feel interesting. I remember feeling so intertwined with my best friends in high school and college, like I needed to talk to those friends every day about every single development in my life. The expectations were so great back then, which made the disappointments between us even greater.

I loved the idea of beginning my book with a friendship between two broken-hearted young women who meet and instantly fill a hole in each other’s lives. But I wanted them to be witness to something terrible, too, so there would be questions of loyalty and truth, memory and sorrow. I used Margot and Thea to flesh out some of my own confusion about why friends really matter, why we need them and how they serve us at different points in our lives.

How much do you consider the likability of your female characters?

It sounds like you didn’t like one of my characters! Ha ha! I have a feeling I know which character may have bugged you because she bugged me at times, too.

I think it’s really important that a reader can empathize with a character even if they don’t agree with all of their choices. In the case of these two friends, I wanted the reader’s emotions to ping-pong. There are moments when you believe in their friendship, and there are moments when you’re questioning why they’re still friends. More than once, I threw a chocolate chip at my laptop screen when one of them would do something selfish, but people can be endlessly disappointing in real life and in fiction.

These friends have spent ten years apart, too, so they find themselves reassessing what they mean to each other when they reunite: how they’ve changed, if they add anything to their current lives, if they still actually like each other. All while feeling indebted to the shared past.

But yes, I want my readers to enjoy my characters, even if they don’t always relate to them. I felt like Thea was incredibly relatable and likeable, but Margot, the glamorous friend, could be selfish and frustrating, the kind of friend you love but sometimes hate. We’ve all had friends like that.

This book is told in a dual timeline. How does that complicate your storytelling? Or does it make it easier?

Dual timeline novels kick your butt! Here’s why: You’re basically writing two separate novels, but you still only have 90,000 words to pull off the story. You must be sneaky about developing the plot and character arcs in both timelines very, very quickly.

In the beginning, I wrote three chapters at a time. Three set in the present (1977), then three in the past (1967). But at the midway point, I realized that I had to go back in time and learn everything that happened between these women before I could understand what happens when they reunite ten years later. The past always informs the present.

I broke the timelines into their own Word docs and wrote them as two separate books for nine months. Then I wove them back together at the end. Dual timelines complicate the storytelling because everything in the past must relate to the future, and vice versa, and you have to find clever ways to insert easter eggs in one timeline that are given deeper meaning and understanding in the other.

But that’s also the rewarding part of writing dual-timeline novels; they give the writer the opportunity to delve deeper into a character by showing them at two different points in their lives. You really start to get a sense of a character’s motivations, their longings, their regrets, and their sense of self. You can also see how history shaped their ideas about themselves and each other, and I loved that.

As an author myself, I have my own tricks for getting the pages to turn. What are yours?

I love this question, and of course, now I want to know yours! One thing I love to use is dialogue. There’s the conversation that the characters are having on the surface, and the conversation they’re really having that simmers underneath. With enough intriguing dialogue sprinkled throughout a story, I try to encourage readers to wonder what’s really happening, and that keeps someone reading.

I always try to leave chapter endings with a question, too, so readers are wondering what the answer is enough that they keep going. We read because we’re curious, so I try to keep the reader wondering what will happen next. A reviewer recently told me that she kept guessing where the story was going, but the characters kept surprising her. That’s a high compliment. If there’s a new piece of information on every page, if there’s something to push the plot forward and characters are intriguing enough, I think readers will stick with you.

How are your own experiences reflected in this book, if at all? Do you incorporate what you know (growing up on Long Island, for instance) or is it all made up?

I was a total townie growing up on eastern Long Island! We spent summers driving through the Hamptons to visit my family in Montauk, also year-rounders. To give you a sense, my uncle was a fisherman, my aunt drove a school bus. My dad was a house painter, my mom was a real estate agent. But they were also musicians and writers, and I grew up on epic stories of Andy Warhol’s wild parties at his Montauk estate and the Rolling Stones staying at the Memory Motel.

That position as a local in a rich summer town gave me such a unique vantage point in which to study the Hamptons. We would drive through East Hampton, and my nose would practically be pushed up against the glass staring at the giant shingled houses with towering privacy bushes and wide pebbled driveways. I grew up on stories of rich people behaving badly, whether it be some lady wearing designer sandals pushing her way to the front of a line at camp pickup or some guy in a fedora demanding caviar at the IGA. (I’m riffing here.)

As I got older and became a journalist, interviewing people on both sides of the income divide, I realized that rich people had all the same emotional struggle that lower income folks did. They just had nicer houses. No, but for real, that tension that exists in beach towns between the people who can afford to buy homes and the people who work in the service industry meeting their needs is an endless fascination for me because I watched it unfold every summer. There are so many misunderstandings that happen between people in beach towns, and I burrow into those tensions and try to give readers a wide lens view of how everyone fits (and doesn’t fit) together.

For this book, I thought it would be interesting to take a wealthy summer girl from the city and pair her up with a local hardscrabble girl and see what happens between them. Because that happens all the time in the Hamptons; a rich kid and local kid end up working as instructors at the same sailing camp. Both are curious about each other, but often, for entirely different reasons. Sometimes those friendships really take off, and I love that.

This book deals with a protagonist who is at home but wants to work, whose husband wants a baby but who isn't sure she wants one herself. Were you thinking about what's happening politically in the US right now as you were developing this thread?

I love how you think! This wasn’t at all in the forefront of my mind, but I do think it was probably bouncing around in my subconscious because I wanted my characters to see their lives as a series of choices. I wanted them to feel empowered and not be afraid to ask the people they love for what they need. In Thea’s case, it’s the desire to put off a second child and begin drawing again. It’s extremely hard for her to ask for this time for herself, in part, because of the pressure she feels to have a bigger family, but also because it’s hard to admit that she needs anything that’s just hers.

Politically, I chose to show women in the latter part of the sixties because women in those times were filled with so much hope about how different their lives would be from their mothers—and Roe v. Wade hadn’t even passed yet. They’re riding the wave of optimism coming from Betty Friedan forming the National Organization of Women, Congress considering equal pay legislation, music challenging conventions of what it means to be a woman. I love Grace Slick’s famous line she’d deliver at the beginning of every Jefferson Airplane concert: “We’re the people our parents warned us about.”

By the late 1970s, many of these women found themselves in the exact same position as their mothers. At home, taking on most of the housework and childcare and longing for more. Women were working in greater numbers, sure, but in 1979, they were making 62 percent of what men earned.

We’ve come so far from where my characters are in 1977, and yet, they were still struggling with what women are struggling with today: Who gets to follow their dreams, and who gets to decide what we do with our bodies?

What is something you wished you knew about becoming an author before you did it?

How much publicity I’d have to do and how much time I’d feel pressured to promote the book on social media. I’m not a shy person, but I’m not someone who enjoys self-promotion. I’ve always been more interested in other people than I am in myself, which is what led me to become a writer in the first place. I write because I like to sit and think and figure things out on a page, not to stand in front of a crowd and try to convince them to buy my book.

But publicity is a big part of the job. With the fracturing of media, authors are expected to get out and sell their work these days, and I’ve had to build it into my publishing cycle. For example, I won’t work on revising my fourth book at all for the next six weeks. I’ll only be out promoting All the Summers in Between. It’s one reason that I started this newsletter; it’ a way for me to connect to readers in an authentic way that felt like more like me. I can share what’s going on in my life, publish essays and give insight into my work in the medium that feels most natural to me.

What is the best part of the writing process for you? The writing, rewriting, editing, outlining...?

I always joke that I write quick and dirty first drafts. It’s what I would do as a journalist. Conduct days or weeks of reporting and research. Then I would get my words down on paper as fast as I could. After that, I’d go back into my rough draft with a chisel, like I’m trying to sculpt some shape out of a piece of marble. That’s the part I love. And that’s exactly what I do with novel writing.

Anne Hull, a former Pulitzer Prize winning journalist for The Washington Post, said at a publishing conference once: “Rewriting is a gift.” That’s how I see revision. It’s this chance to make everything better, and after the story is set into place, I tend to revise thematically. I’ll do a revision that focuses only on one character, where all the dialogue is working to show her development. Then I might do a revision that looks only at chapter beginnings and endings, another critical way to keep readers turning pages.

I don’t outline much at all because I find that it’s a waste of time. I never stick to the outline, and I write for discovery. It can be inefficient. There are times when I toss out half of what I wrote one day, but there may be three graphs there that become essential to pushing the plot forward.

What's the hardest part of the process for you? The thing you have to do but maybe dread.

It’s when I go into a book thinking that it will be about something powerful but when I re-read what is on the page, I’m incredibly disappointed. It’s insanely difficult to translate all of the depth and ideas you have for characters and setting and story and make it shine through on every page. With all three of my novels, there has been a point where I lost hope in my story. I’ll chastise myself for not being a better writer, for the book not feeling ambitious enough. In these moments of self-doubt, I typically go for a run, quiet the negative voices in my head and sit down the next morning with a fresh cup of tea. You just have to write through it, I’ll tell myself, like you always do. It’s just going to take more time than you want it to.

Then the book always gets better and stronger and smarter—and a little closer to my initial vision. When I went through this phase during the writing of my fourth book, my husband said: “This is just part of the process. You always hit this point.” He’s right, and now that I know that, it’s so much less scary.

Who would play Thea and Margot in the movie adaptation of this book?

Someone else recently asked me this, and it was easy to figure out Thea. I see Elle Fanning as down-to-earth, local girl Thea looking for something more in her life. Margot, the wealthy city girl, was harder for me to cast, but in the end, I settled on Emma Roberts. She has that glam look to her, but she also has a face that reflects an inner struggle which feels very much like Margot to me.

Can you tell us anything about your next book?

Yes! It comes out next summer, and it’s about three adult sisters growing up with a feminist icon as a mother and a United States senator as a father. When they’re called home to Martha’s Vineyard one summer and told unsettling news, the sisters are forced to reckon with who they thought their family was and who they’ve become. I loved being on Martha’s Vineyard for that one. It will be out next summer, but living for an entire year with three tense sisters was draining! Sometimes I’d go to school pick up with my eyes crossed and think: These sisters need to stop fighting. But I truly love it, even on those exhausting days, I love being in my invented worlds.

You can find Amy Odell on Substack, where she authors the fashion and culture newsletter Back Row.

“More than once, I threw a chocolate chip at my laptop screen when one of them would do something selfish…” I love that imagery!! It is so classically you, Brooke!! :)

Happy Publication Day! And great interview!